Problem solving with process thinking - part 2

- Authors

- Name

- Andy Cao

Table of content

Beyond the Basics of Process Thinking: Aligning Multiple Processes and Stakeholders

In our previous post, we touched on process thinking—a method of listing activities in a chronological, logical sequence to spot potential problems or improvements. We also hinted at how some steps are product activities (directly delivering value to your end users) while others are Enabling Activities (the behind-the-scenes tasks that enable the final product or service).

Real-world undertakings—whether software development, event organisation, or daily restaurant service—rarely follow a single, linear list of tasks. Instead, multiple overlapping processes happen in parallel, involving various teams or stakeholders. This second post builds on the fundamentals by demonstrating how to manage multiple processes without losing sight of either your product activities or your enabling Activities.

From Single Process to Multiple Processes: Why It Matters

In a simple scenario our previous restaurant example, we can list steps such as greeting diners, taking orders, cooking food, and then clearing tables. That approach highlights what gets done and when—ideal for clarity. Actual operations typically involve many parts:

- Front-of-house staff taking care of seating, order-taking, and customer satisfaction in the front house.

- back-of-office staff juggling ingredient preparation, cooking times, plating, and cleaning in the kitchen.

- managerial roles handling payments, planning, or .

Each group follows its own process, often interlocking with others. For instance, the kitchen can't start cooking, which is a typical product activity, until certain project logistics are in place—like having fresh ingredients, tested recipes, or working equipment. Meanwhile, front-of-house might rearrange tasks based on busy times, reservations, or special requests.

By seeing how roles and activities intersect, we'll discover:

- Mandatory tasks that must be done in a fixed order (e.g., cleaning a table before seating guests).

- Discretionary tasks where timing is more flexible (e.g., deciding whether to upsell dessert immediately or wait until guests finish their entrées).

This interplay of roles and responsibilities creates multiple, parallel processes. When well-coordinated, the result is smooth service (or product delivery). When they clash, chaos ensues—leading to missed steps, bottlenecks, or customer dissatisfaction.

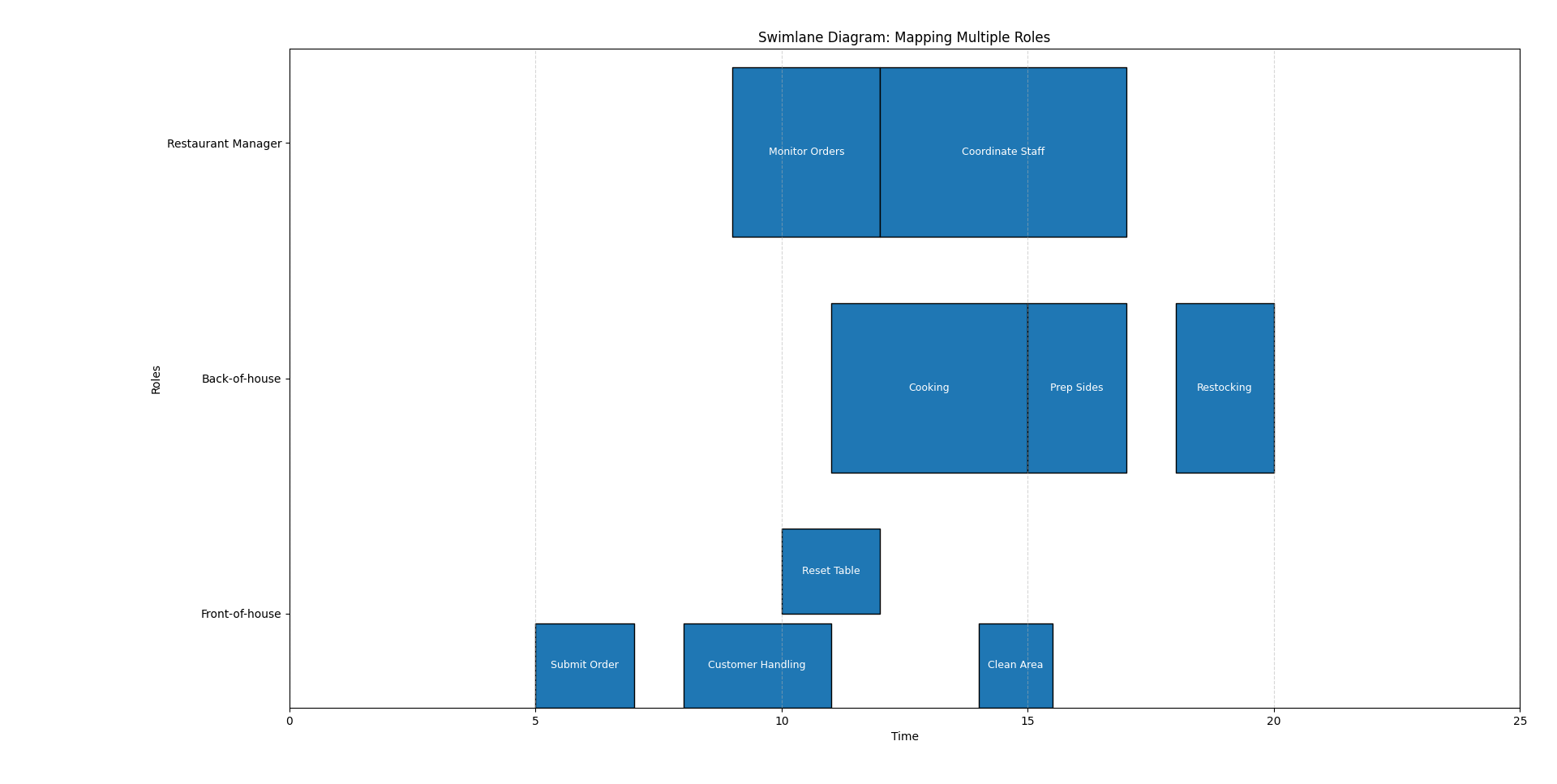

Mapping Multiple Roles: The Swimlane Concept

A swimlane diagram is a useful method to visually distributes each role, function, or department into its own “lane”. Within each lane, you can list the tasks (both product and enabling activities) allowing others to see:

Where tasks overlap

- For example, when a waiter submits an order, it represents a point of intersection between the waiter's customer interactions and the kitchen's responsibilities—which include both cooking and operational tasks such as restocking or planning menus.

Who waits on whom

- The restaurant manager might delay taking new orders if the kitchen is under pressure. Similarly, the kitchen may hold off on preparing certain dishes until the waiter confirms that diners are ready for their mains.

Which tasks run in parallel

- In a more realistic setting, a waiter might simultaneously manage multiple tasks—taking orders, processing payments, and resetting tables—while the kitchen preps sides for several tables concurrently.

Without a diagram, it's easy for teams to lose sight of how their responsibilities interconnect, especially when product and project tasks blend together (such as redesigning the menu while handling active orders). A visual map ensures that no team operates in a silo, fostering a cohesive, consistent service.

Pressure Points in Multi-Role Scenarios

In the first post, we explored how mandatory and discretionary dependencies highlight “pressure points.” Let's flesh out these concepts further when multiple processes and stakeholders interact:

Hand-Offs Across Departments

- Mandatory: A chef cannot start cooking (product activity) unless fresh ingredients are purchased, inspected, and stored (Enabling Activities). If the purchasing process lags, the kitchen can't operate—stalling the entire restaurant.

- Discretionary: Chefs might prepare sauces ahead of time (a more flexible, “discretionary” approach) or wait until mains are nearly done. Neither sequence is strictly enforced by logic constraints, but each has pros and cons (e.g., freshness vs. readiness).

Parallel Processes

- Mandatory: A table cannot be seated again until post-service cleanup is finished. If the dining room tries to seat guests too quickly, the entire experience suffers. This cleanup is arguably a Enabling Activity (facilitating the next meal).

- Discretionary: Staff might choose how soon to present the dessert menu—immediately after clearing mains or after a brief pause, depending on diner cues.

Timing Collisions

- Mandatory: If a particular event (like a live cooking demonstration) starts at 7 PM, all preparations—equipment checks, staff readiness, final rehearsals—must be completed beforehand.

- Discretionary: Folding napkins or restocking non-critical supplies might happen in any sequence, as long as they're done before service begins.

When your restaurant or project grows, you'll see more collisions. For instance, if marketing schedules a special promotion on a day the kitchen is short-staffed, you've got a conflict between product ambitions (serving more customers) and project limitations (staff scheduling or supply chain issues).

Product Activities vs. Enabling Activities

The key distinction in multi-process scenarios is between product and Enabling Activities. Product activities are the core tasks that directly impact the end-user experience (like serving a meal or processing a payment). Enabling Activities are the behind-the-scenes steps that support or enhance the product (like inventory management, staff training, or equipment maintenance).

- Product Activities: Taking an order, cooking a dish, plating food, presenting the bill—anything the customer directly engages with.

- Enabling Activities: Inventory planning, staff training, marketing promotions, equipment maintenance, financial accounting—necessary to support or enhance the product but not always visible to customers.

Process thinking helps you balance these two kinds of tasks so neither is overlooked. For instance:

- Product tasks (actually delivering the upgraded ordering experience) might highlight gaps if the supporting project tasks (like system updates, user acceptance testing) weren't fully completed.

- Enabling tasks (retraining staff on new technology) must occur before your new ordering system (a product feature) can be rolled out.

There are times where enabling activities can be considered as a standalone project (like a kitchen renovation) or a product feature (like a new menu item). The key for this distinction is whether the task directly impacts the end-user experience or is a behind-the-scenes improvement.

Example: Software Development Meets Restaurant Logic

While a restaurant is a tangible, everyday example, the same process concepts extend to software development or event planning:

Front-End

- Product Activity: Designing the UI or user experience.

- Enabling Activity: Collaborating on style guides, preparing assets, or scheduling design reviews.

Back-End

- Product Activity: Ensuring each function or data operation works when a user clicks a button.

- Enabling Activity: Maintaining servers, updating libraries, or fixing infrastructure bugs behind the scenes.

QA / Testing

- Product Activity: Verifying that each feature meets end-user requirements (e.g., no crashes).

- Enabling Activity: Tracking test cycles, documenting regression tests, managing bug logs.

In each area, adopting multi-process thinking clarifies who must do what and when. If QA can only test after new code is deployed to a staging environment, that's a mandatory step. Meanwhile, when QA decides to run load tests or precisely how to group them can be discretionary, provided it meets the overall release deadline.

Tips for Handling Multiple Processes

Identify Roles, Responsibilities, and Activity Types

- List out who is involved and separate product (user-focused) from enabling tasks in each process.

Flag Mandatory vs. Discretionary Tasks

- Mark strict, non-negotiable dependencies (clean table first, then seat guests) vs. flexible tasks (restock sauces at any time before service starts).

Maintain Regular Check-Ins

- Brief stand-ups or daily huddles help each team keep track of new product requirements, project deadlines, or shifting priorities.

- This is especially critical when tasks in one department can stall others.

Keep a Central Process Map

- Even if each team has its own sub-process chart or tracker, align them in one overarching reference. This prevents duplication, confusion, and missed hand-offs.

Review and Refine Continuously

- As your business evolves—expanding menus, changing technologies, new team members—update your process maps. Process thinking is an ongoing practice, not a static diagram.

Why This Matters for Your Overall Business Process

By recognising multiple processes at play—each with its own mandatory and discretionary dependencies—you build a powerful lens for decision-making:

- Reduces Surprises: Early identification of constraints (like essential ingredients running low) prevents last-minute chaos.

- Enhances Accountability: People know precisely where their tasks intersect with others', be they product-facing or behind-the-scenes.

- Improves Efficiency: Distinguishing product from project tasks prevents over-investing in one area at the expense of the other.

- Minimises Bottlenecks: A delay in one process doesn't spiral out of control if everyone is aware and can adapt their discretionary steps accordingly.

A restaurant might seem a world apart from software, healthcare, finance, or events—but process thinking unites them. Whenever different groups share resources or pass responsibilities, mapping both product and project tasks clarifies who owns what and when.

Final thought

In our first post, we touched on the fundamentals of process thinking with a single series of tasks. Now, we've expanded the picture: real operations typically involve multiple processes, each belonging to different teams or departments, and each containing a blend of product and project activities.

By labeling and mapping these processes—identifying roles, clarifying mandatory vs. discretionary steps, and maintaining central references—you equip yourself to handle even the most interwoven challenges. The result is a more resilient, responsive operation that quickly adapts to unexpected changes or demands.